In the year 1974 American artist Anne Truitt (*1921) set herself the task of writing every morning when she woke up. There was no time limit to how long she would write, just for as long as she wanted or could around her responsibilities. She started writing as a year-long project because she felt there was little integration between herself and herself as an artist. In the journal, she is referring to the self that is responsible for the domestic chores of maintaining a household, being a mother, and herself as an artist. She goes on to say that as her sculptures began to gain recognition, she felt it was harder to see herself: “It slowly dawned on me that the more visible my work became, the less visible I grew to myself”. Over time, Truitt transformed her integration of the self, she created a space for her thoughts and the self that she didn’t want to include in her work. She continued to create large scale works, divorced her husband and raised her children.

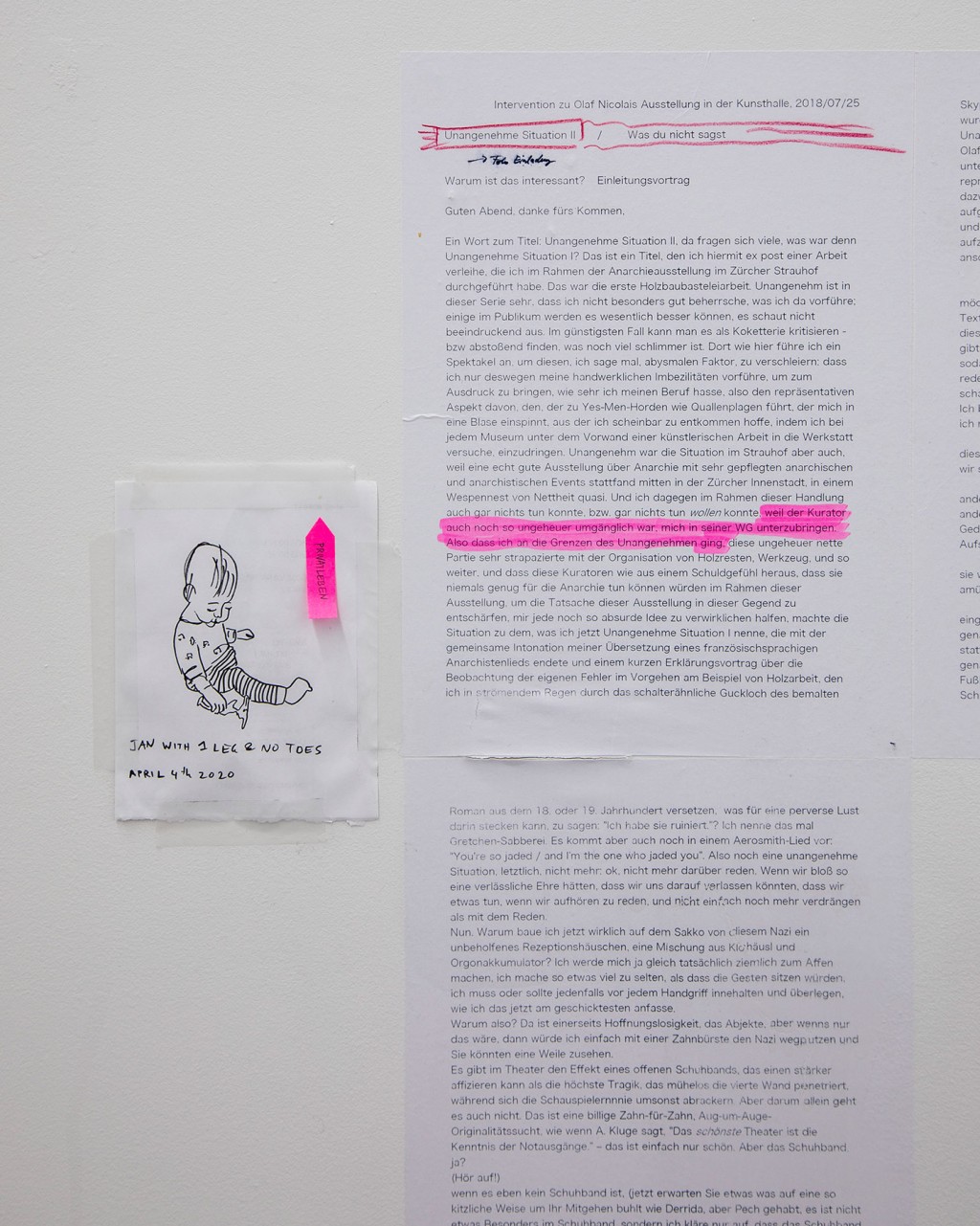

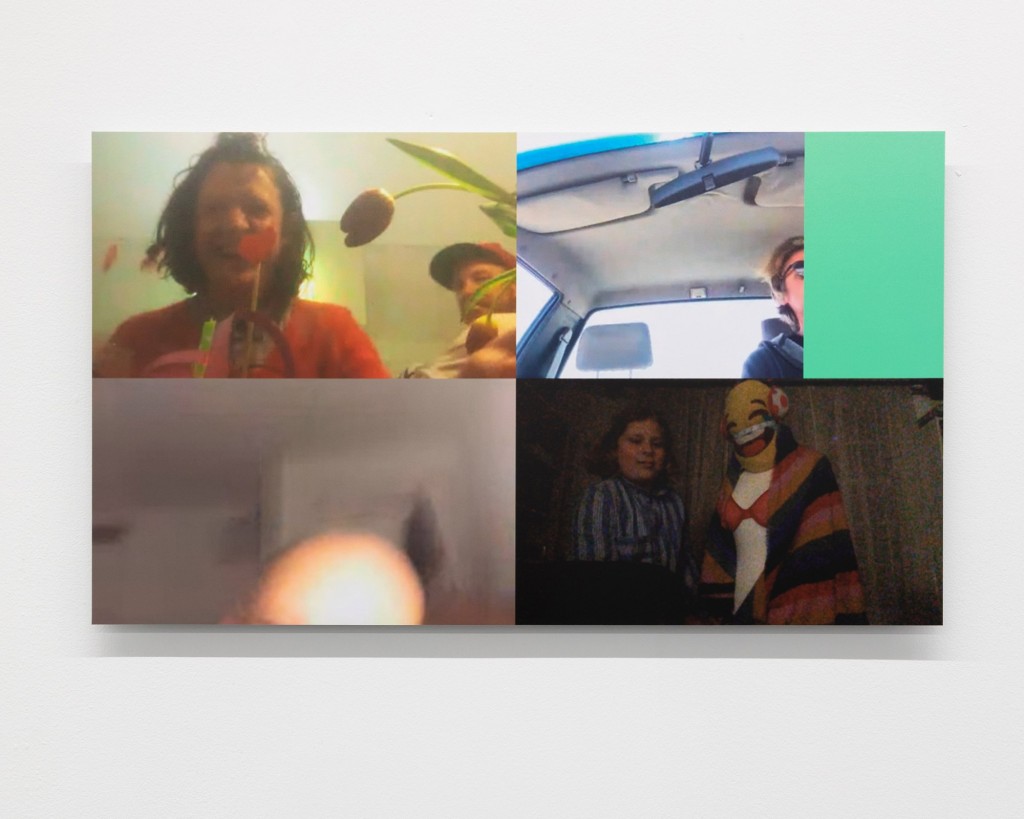

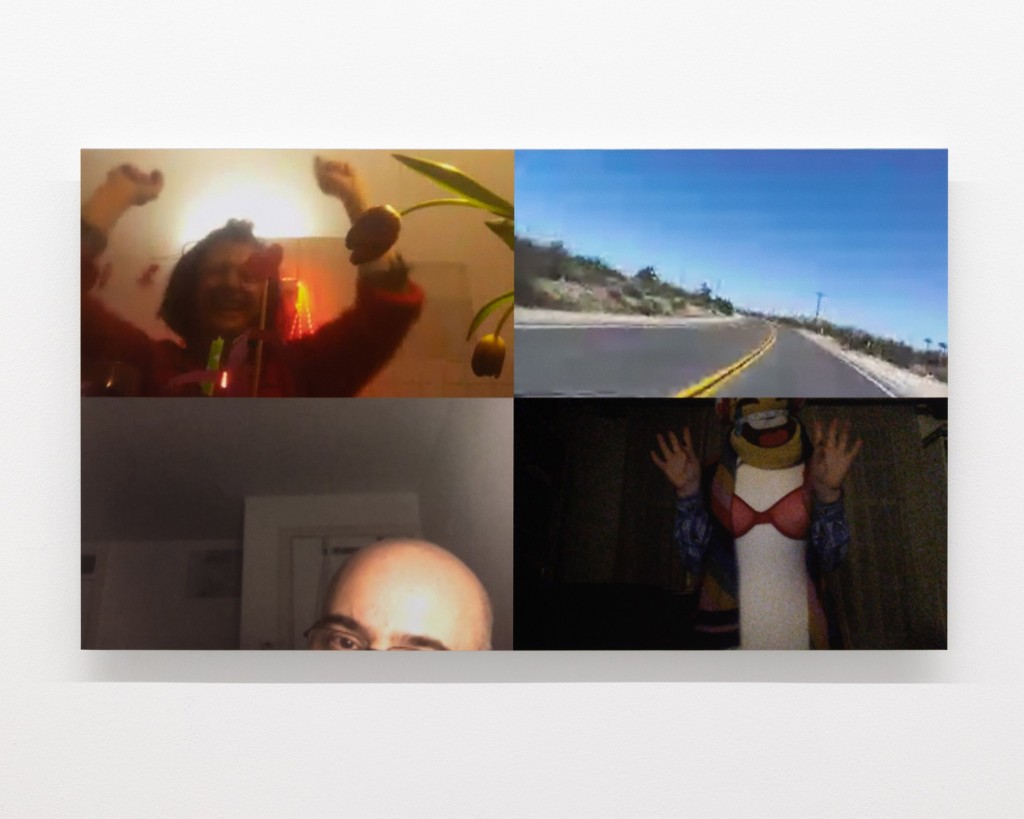

In 2014, I participated in the group exhibition Revelry that Tenzing Barshee curated at Kunsthalle Bern. “Private and public life are intertwined today more than ever before,” he wrote in the press release, “putting our notions of intimacy in constant fluctuation.” It seems felicitous that six years later, Barshee’s exhibition Revelry transforms into Reverie. During the recent pandemic and state-ordered isolation, private and public life merged into a single laggy, glitched experience, not dissimilar to how I recall the opening of Revelry.

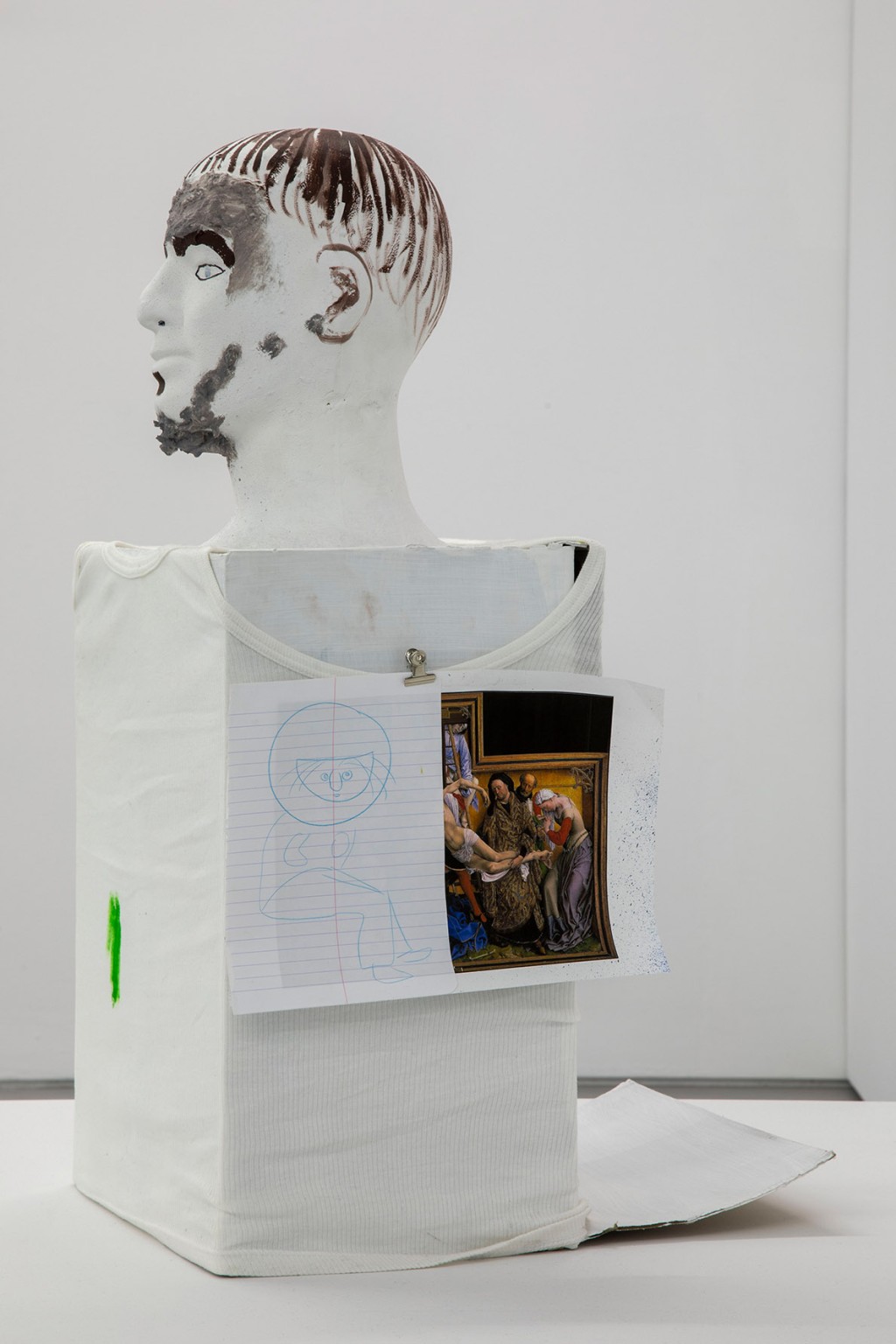

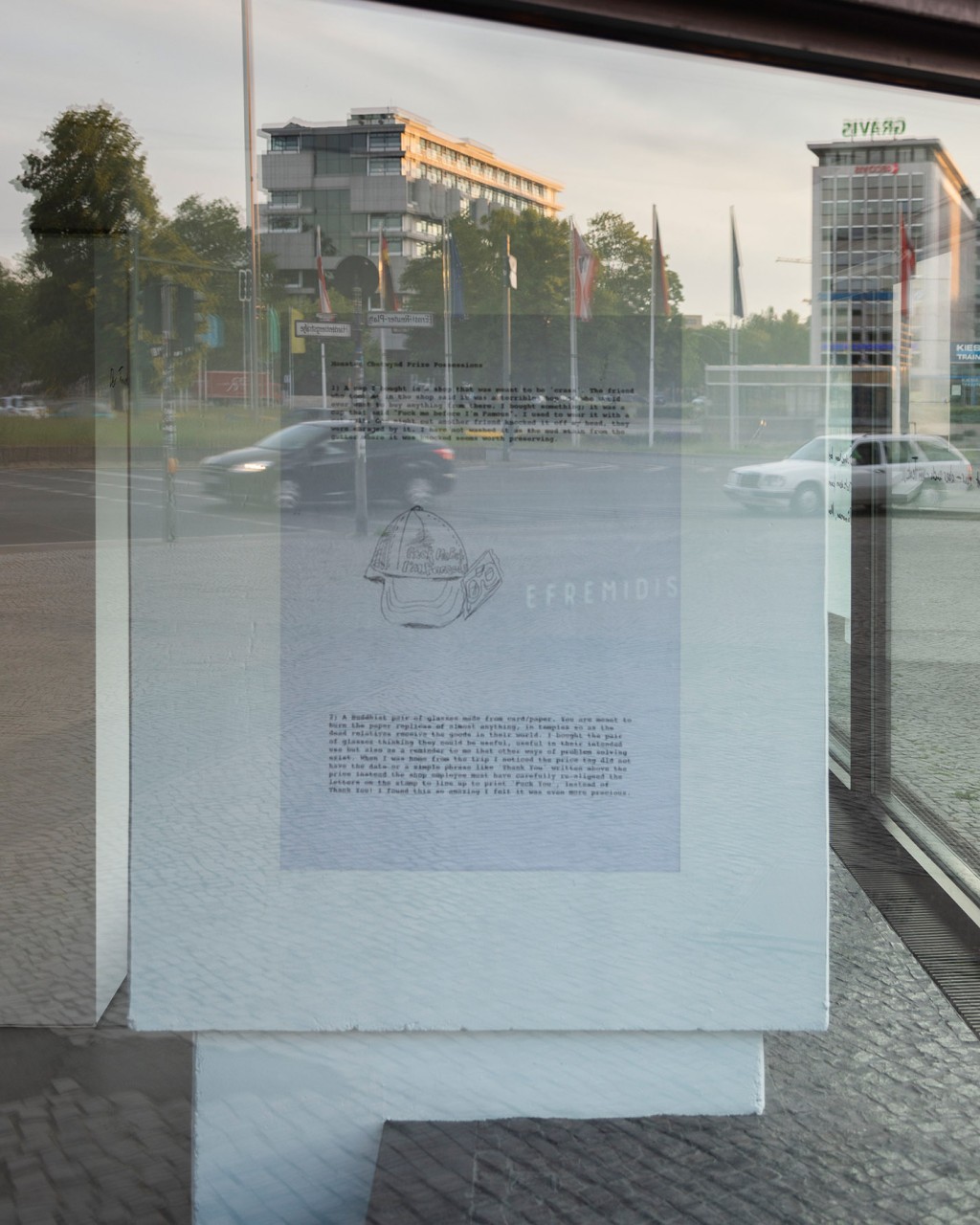

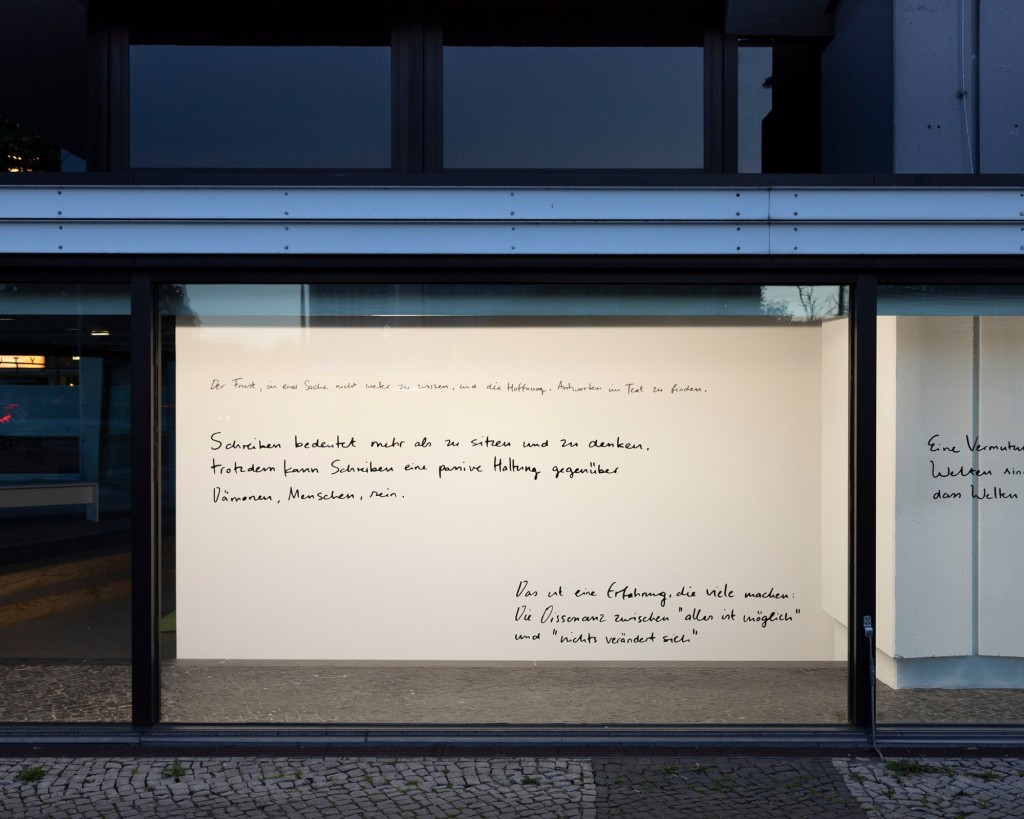

Pippin Wigglesworth’s contribution to Revelry was the publication Räume, written like a journal, titled by which day it was, followed by a detailed description of the various rooms he inspected as part of his job day after day; these passages of interiority resonate an entirely different narrative today. His contribution to Reverie asks whether “text and its subsequent publication manages to make contact with those whom we love, have loved and those that ceased to exist.” Before his AIDS-related death in 1984, Michel Foucault spoke of an idea for a book titled “technologies of the self.” He described it as “composed of different papers about the self..., about the role of reading and writing in constituting the self...” Does one write to write or does one write to be read? Anne Bower explores this concept eloquently through letter writing in her 1996 Epistolary Responses: Letter in Twentieth-century American Fiction and Criticism.

Traditionally associated with women and with the “private” as opposed to the “public” sphere, the letter form engages many feminist issues. At the same time, with its emphasis on the act of writing and writing as an act, the letter permits exploration of postmodernist questions. The back and forth of letters, their desire for reply, their incomplete ownership of information, their concomitant play on ideas of absence and presence, and their apparently personal and private nature, model an interactive openness (although one always knows, paradoxically, that this seeming openness can be used for manipulation and deception).

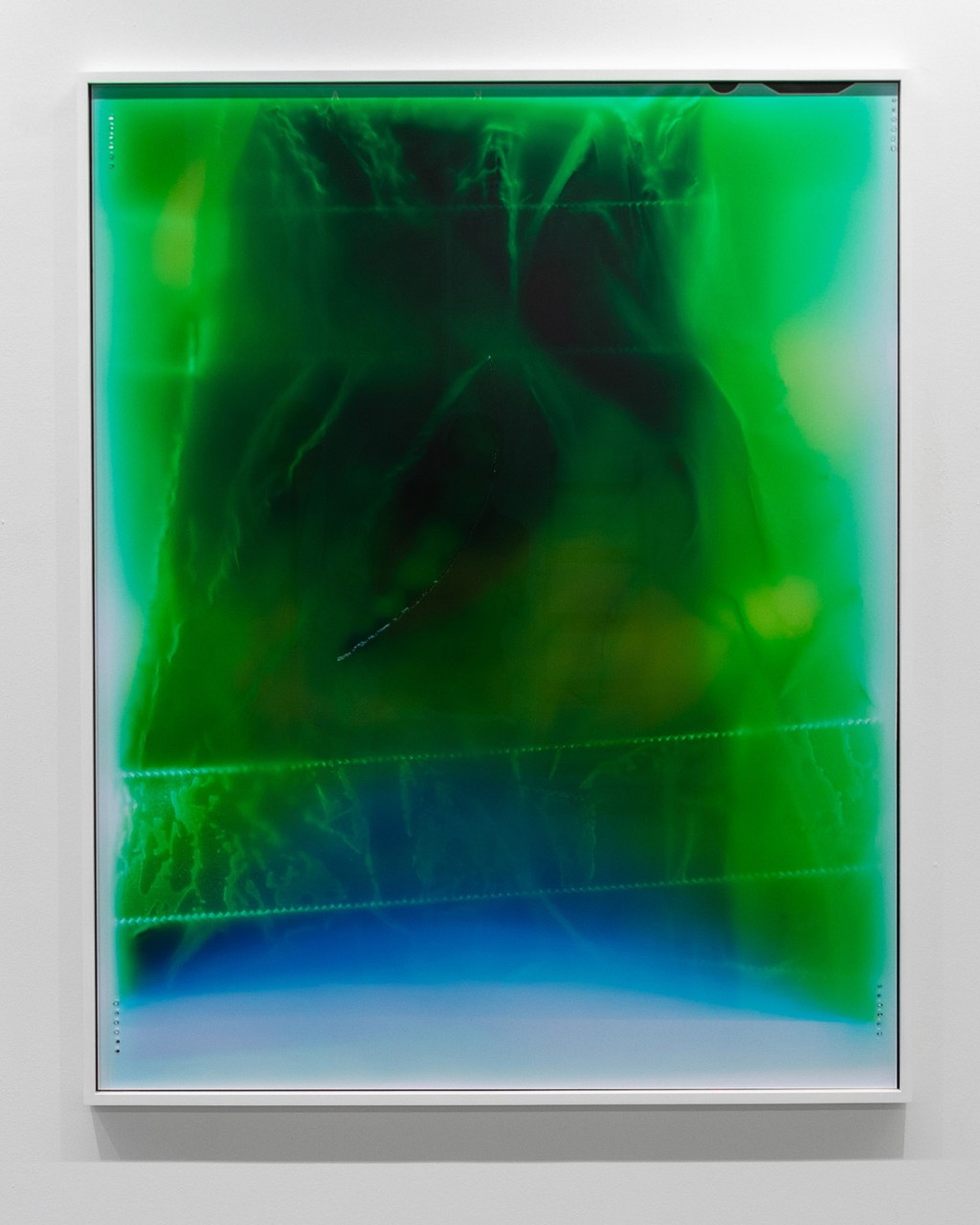

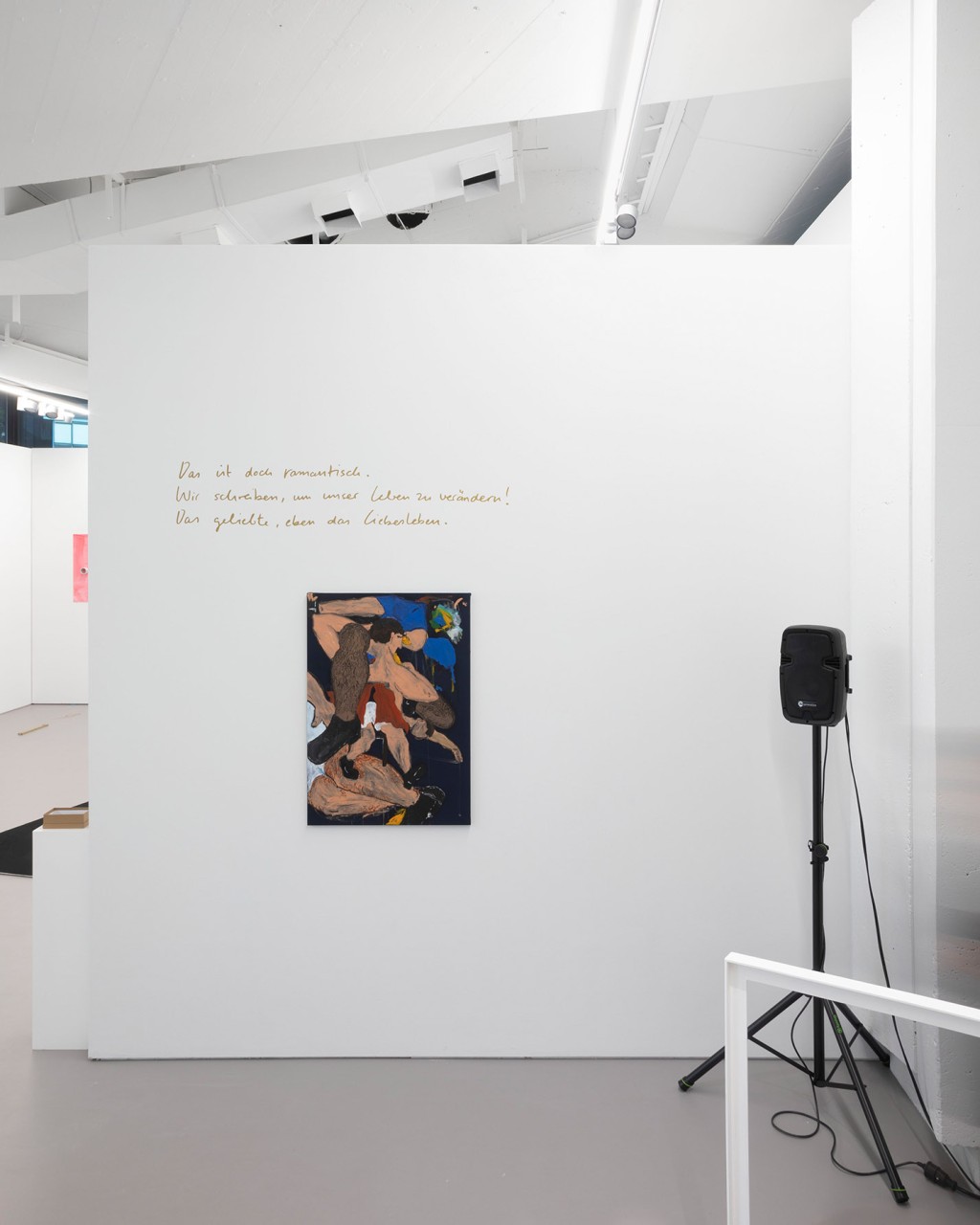

Reverie won’t have a traditional opening, the exhibition comes together in a moment when movement is still restricted in many ways. When thoughts and everyday lives have been streamlined even further into a single state of existence. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau writes in the final years of his life, whilst living in exile “There, the noise of the waves and the tossing of the water, captivating my senses and chasing all other disturbance from my soul, plunged it into a delightful reverie in which night would often surprise me without my having noticed it.”

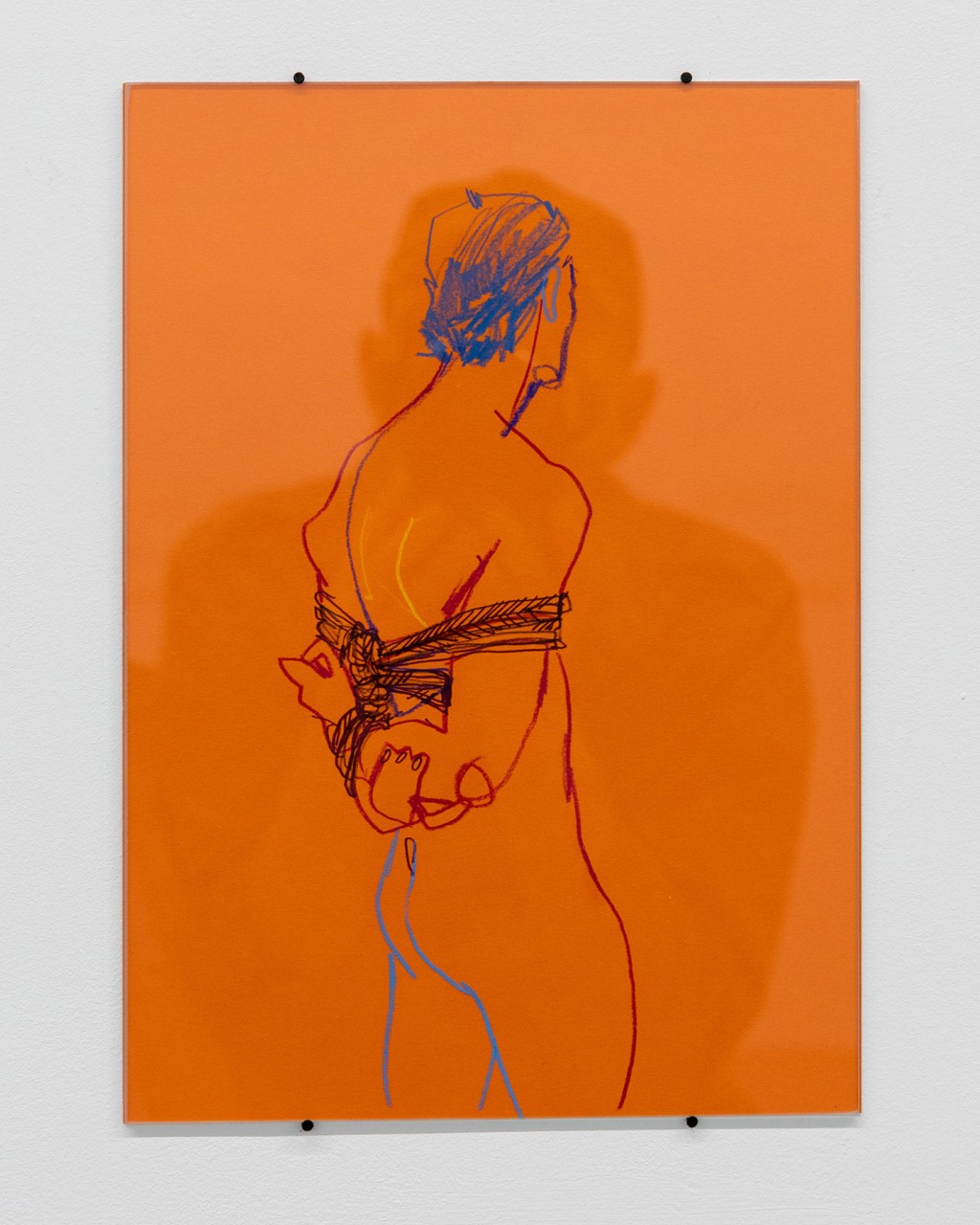

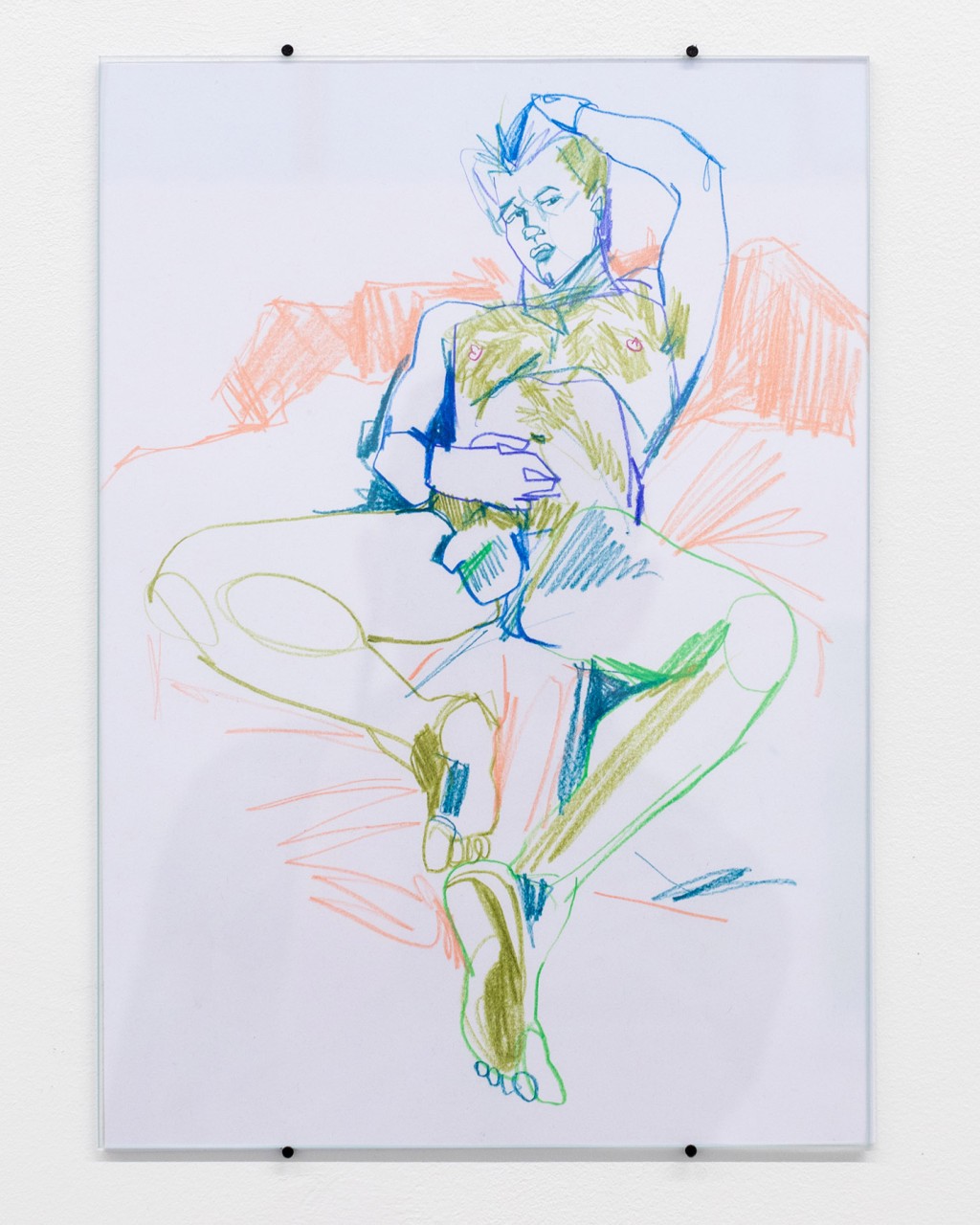

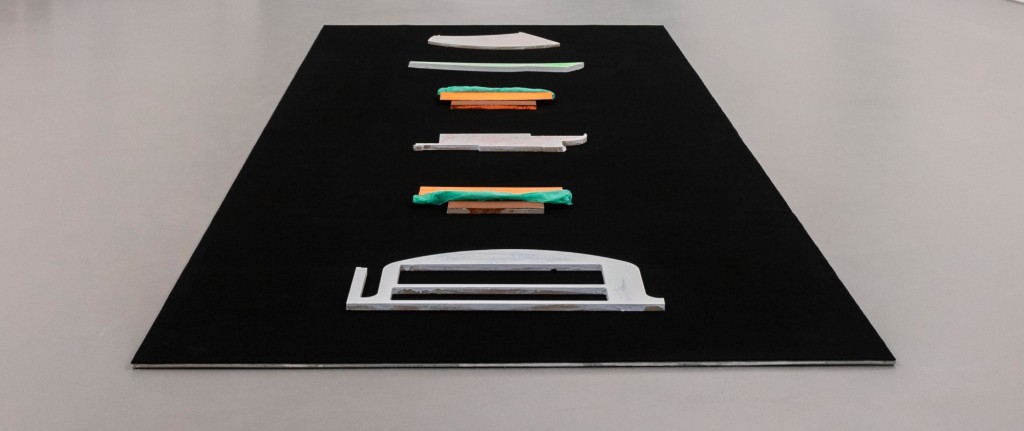

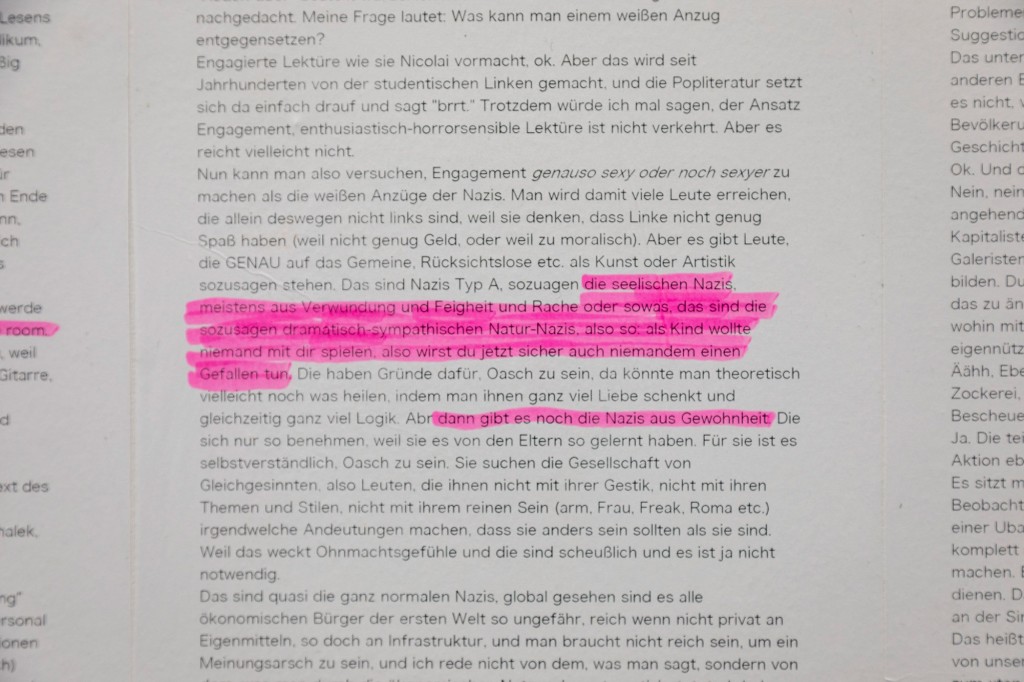

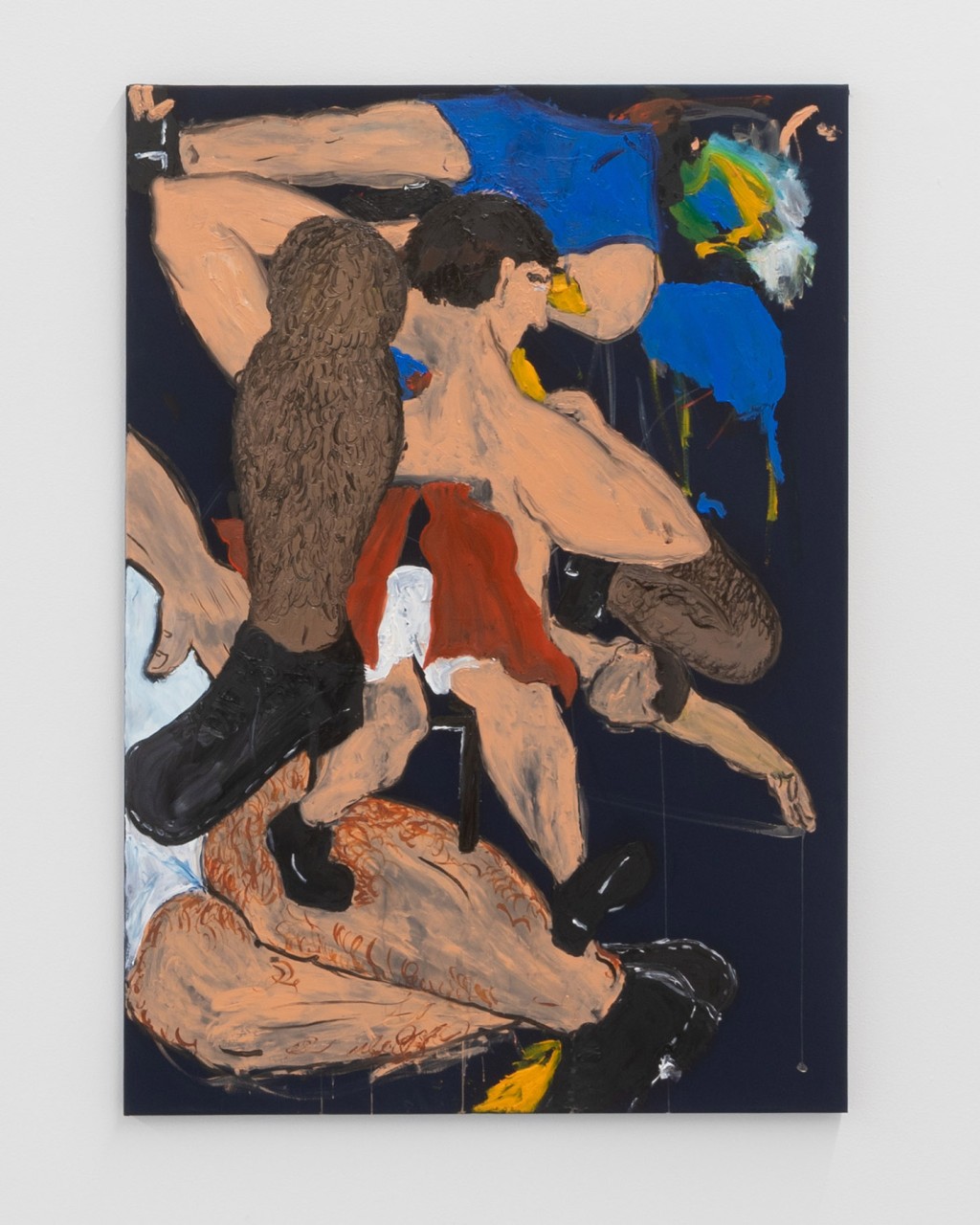

The narrative running through Reverie is reflective of that changing light, as more and more galleries and institutions open up again, works and words are once again physically visible to experience, bound up as they should be, in bodily sensations, color and pop music. The works in Reverie are soft and awkward, some are rude, intense, harsh and tough, hard even. Much like the ebb and flow of everyday life.

There is no substitute to actually being present.